Invisible Cities: Mitigating the Bird Strike Problem

April 25, 2024 | By Rose Latter

It’s a global crisis, largely unseen by us city dwellers. It happens way above us, at night, and is cleared away by caretakers before our morning rush to work. Maybe we witness one or two single episodes on our windowsill or patio door, but we are missing the big picture. Twice a year, while we sleep, millions of birds all over the world are migrating through our cities on the way to and from their overwintering grounds and summer breeding spots. But, during their travels, millions of birds are killed in collisions with glass buildings that they can’t see. As this threat to global ecosystems becomes increasingly clear to people around the world, built environment designers can act to help solve the bird strike problem, rather than exacerbate it.

Humans and birds have flourished together for millennia, and their constant presence in our world reminds us of our connection to the wild in our sanitised urban landscape. We are so attuned to birdsong that deep in our subconscious lies a part of our brain that associates the sound with safety. When the singing stops, the quiet space left behind indicates that there is a predator threat nearby because the birds have seen it and flown away. We are so innately sensitive to this alert that our hearing has evolved to receive the precise frequencies transmitted by birds. In the modern world, its presence is proven to be a calming influence on our human subconscious in times of stress, and consequently, some hospitals, GP surgeries, and dentists play birdsong very quietly in their waiting rooms to create a pleasant environment.

Many traditional cultures have origin myths associated with birds, and those still resonate for us today. We think of owls as wise, of storks bringing babies, and of doves as symbols of peace. In folk tales and songs throughout the world, birds represent human characteristics; think of the eagle’s strength and the bluebird’s joy. How many sports teams can you guess with birds as their emblem? Until very recently, a beloved New York city zoo escapee Flaco the owl regularly featured in the news as a symbol of survival and independence as he made Central Park his home.

Avian life is an essential part of the planet’s ecosystem in a practical sense too. They scavenge to control pests in cities and nature, and they pollinate flowers and spread seeds to enable plant life to flourish. Varied species of birds have evolved in symbiosis with the landscapes they traverse, transforming and maintaining delicate habitats such as marshland, woodland, and heath. If their numbers decline to critical levels and species become extinct, the whole balance of nature is disrupted along critical migration routes from beginning to end.

Once we become aware of nature around us, we begin to realise we are part of something bigger beyond the limits of our perception. There is so much of the world we can’t see, but there is an ultraviolet and electromagnetic world, imperceptible to our human senses, where birds and insects exist (as seen in this video). Some species can echolocate, navigate by the earth’s magnetic field, and have evolved receptors in their eyes that extend beyond the colour spectrum that our eyes can detect. They use these capacities to communicate, display their courtship finery, and find food.

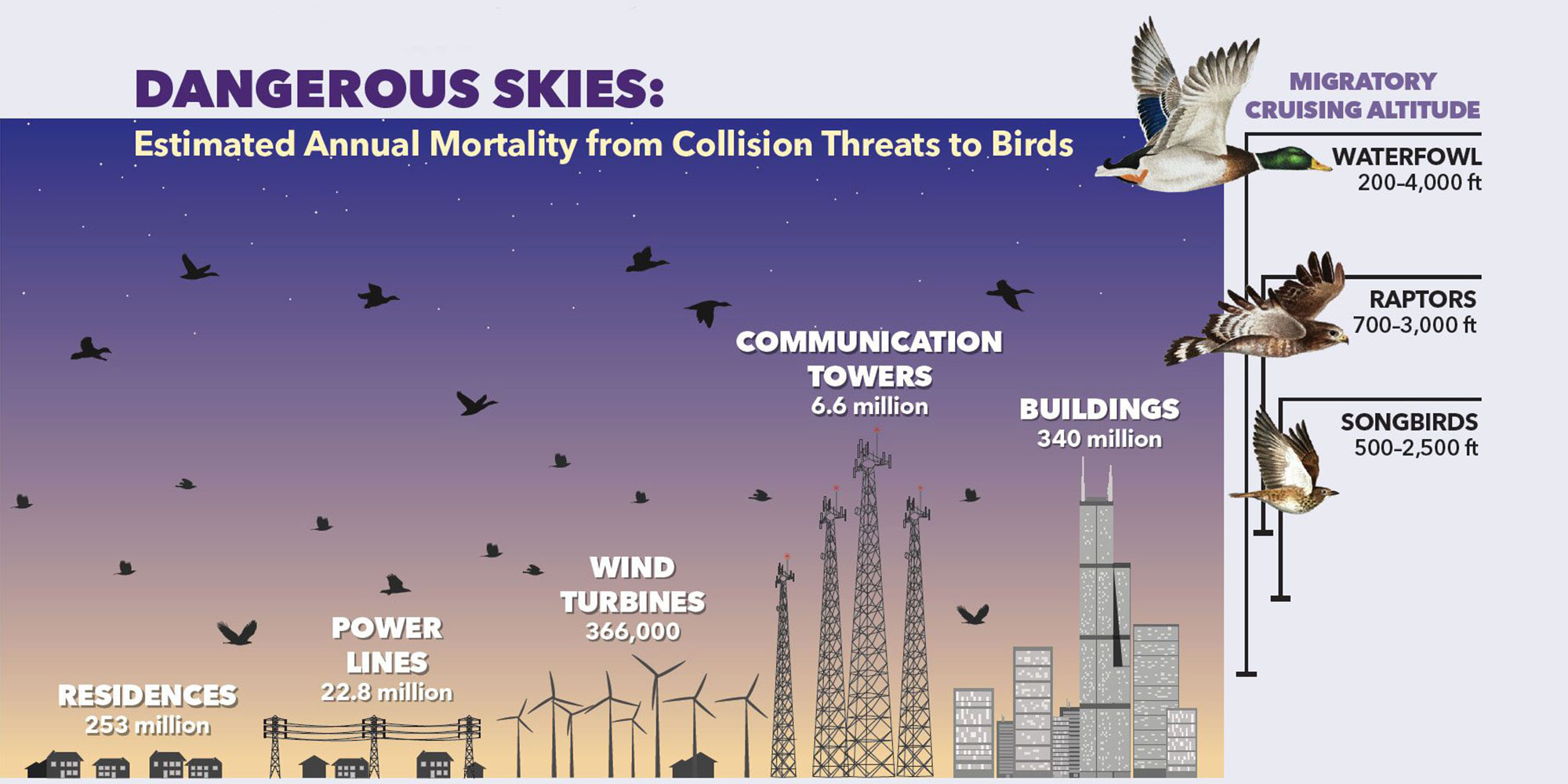

Unfortunately, our world of glass is invisible to birds, with devastating consequences. Birds have not evolved to understand visual clues such as window frames or door furniture that we interpret to stop us from walking into glass panels. All birds see is the reflection of the sky or trees, which they perceive as open space, and they fly headlong into the illusory solid. While many species of migrating birds fly at heights of hundreds of feet, this is not just a tall building problem. Domestic buildings also kill many millions of birds, both native resident species and migrating ones, particularly songbirds. The issue is not just felt locally, but more expansively along migration corridors on every continent.

As our ecosystem becomes more precarious for birds, it becomes riskier for us, and the numbers are staggering. Up to one billion birds in the U.S. and Canada are estimated to be killed annually. In response to this crisis, there are global calls from increasingly concerned citizens, scientists, naturalists, and ecological foundations for action. Legislators in North America are bringing in more stringent building design codes that will soon be enforced by laws. Europe and the rest of the world will follow. Large investment companies can see a gap in this market and are actively seeking to burnish their ecological credentials by funding innovative technological advances to address the situation.

There are some efforts to mitigate the problem with design and manufacturing solutions, but currently the thinking is not yet coordinated enough, and research efforts are often siloed in universities. Small-scale applied glass solutions have not made a significant impact yet, can be unsightly and costly to implement. The Audubon’s Lights Out program, which encourages building owners, managers, and homeowners to turn off excess lighting during the months of bird migration to help birds have a safe passage between their nesting and wintering ground, has some beneficial effect but relies on compliance to implement.

Promising Gensler examples of active measures and new technologies to mitigate bird collisions are in Chicago. Our work with Sterling Bay on 1229 W Concord Place, a life sciences development in the heart of Lincoln Yards, is the first high-rise in the city to implement a bird-safe, fritted glass façade that helps to protect millions of migratory birds passing through the city. The Hub at Prairie Shores also gives special consideration to the migratory paths of native birds with the use of a bird-safe acid etched glass, creating a unique cloud-like aesthetic on the facade.

As a company and as individuals, we have a moral and ethical ecological imperative to protect and support the environment and create places where humans and biodiversity can flourish. As designers and trusted client advisors, we also have a professional obligation to guide our clients through potential solutions and navigate the legislation. What if we could use our thought leadership and connections to make a difference, to develop glazing visible to birds but invisible to humans?

We can use the power of our ingenuity and connections to stay ahead of upcoming legislation. Gensler has the research, strategy, and globally connected capacity to change the world through the power of design by partnering with specialised knowledge centers and manufacturers. With coordinated research, we could help solve the bird strike problem and provide a legacy solution to benefit ecosystems in cities worldwide.

For media inquiries, email .